Rob Bignell arrived at Starfarer’s Cafe with this fantastical tale of a strange custom among several far-flung alien civilizations – a race to see who can fall into a black hole first. What would you do you if you were in such a race? What if losing the race was the only way to win?

Even before the sun rose, Evod and Nevar prepared themselves for the race. Silently, they inventoried supplies, examined their craft’s hull and unpacked Nevar’s ceremonial suit. Evod inspected each item with a drill instructor’s eye, discovering problems that really weren’t. As Nevar quietly assisted, her brother tapped here and there, scrutinized with the spectroscope, and fidgeted over adjustments. Then came the time for Nevar to don her suit. First the compuvisor went on, followed by the inertia dampener ensemble with gloves and boots, each task done after a short chant as prescribed by tradition. Despite her magnificence in the resplendent suit, Nevar still felt like the adolescent girl she really was, not a daughter of the great pilot T’sohg.

Nevar tried to clear her head, but just like those times when the lonely beauty of the homeworld’s moon had beset her heart and she’d had to convince herself that the sun would rise again, those fears resurfaced. Though she had nagged their unconventional father to teach her piloting, her goals were narrower than Evod’s. Worse, her victory that day was as likely as combining a planet and a star; the latter would always consume the former. Still, she knew of the need to honor those who like her father had tried and failed, and of the need to achieve what men like him had dreamed of, if only for their memory.

“We are of the gifted class,” Evod told her. “Father would want us to compete in this tourney, even if we are not ready.” His body canted forward, like a Cetian cat leaning a moment before the pounce. “They speak badly of him, say he was a poor pilot, that he was frightened. We will prove them all wrong. Tonight they will say, “Did you see how T’sohg’s daughter flew? He could not have been a bad pilot, for who else would have taught her such skills!”

She examined her brother’s young face and wished he were old enough to fly in her stead, but the tourney’s traditions were strong. “Don’t pressure me, Evod,” she said, her voice strained. “I will do the best I can.”

“You must do better than your best. Remember to ride the tidal forces. Always adjust in advance for large objects caught in the gravitational pull. That means other craft as well as asteroids.”

Nevar’s back ached, and she tuned out her brother. She wished for a friend to tell her thoughts to; she had needed one ever since her father died during the last tourney a year ago, but now that Evod was head of the house, his single-mindedness in regaining his family’s pride prevented it as all they did was train. For the time being, her inner ear would have to suffice. Odd, she thought, how on her homeworld the males made the decisions while the females made the sacrifices.

Still, she understood Evod’s anger. Her father had been a great pilot, and although she believe that he’d not been frightened at the end but rather had made an adverse course correction, to tell anyone of such a theory would invite even more unfavorable speculation. She thought that perhaps the reasons he wanted to fly this tourney was to find answers to her own questions.

Slowly their competitors emerged from the dozens of craft at the spaceport. The age and experience of the many contestants unsettled Nevar. There was M’sitpab, representing the wealthiest of the Regulan families, and Pyx, member of a tentacled species that frequently won the tourneys because their additional dexterity allowed swifter response times, and T’Sirahcue, an Altarian, last year’s second place finisher and the new favorite.

Nevar nervously separated the tools she needed for the flight, and Evod, finally quiet, helped. She admitted her family’s craft, a sleek saucer powered by duo artificial singularities that warped and folded space so they could outrun even light. The others around them had begun performing the same preflight checks that she and Evod had done hours before, and soon all the port seemed a blur of activity, like a rain flurry with drops flashing in every direction.

She tried observing the others in action, watching their repetitive and certain motions, but Evod, sensing his sister’s inattentiveness, herded her into the spacecraft. “Focus, focus!” he snapped, and she knew he was right, that she must stop behaving like a child at a sucrose stand.

A voice crackled over the intercom. “So young one, what kind of ship is that? I’ve never seen such a craft?” The voice was ragged, possessing a course timbre.

“This is the craft of the T’sohg family,” said Nevar, her voice filling with pride. “It is the fastest craft from the planet Lautir and can achieve light speed in 2.8 microterms.”

“That slow, is it young one?” the voice said. “Then perhaps you would like us to pull your craft through this race?”

Evod swiveled toward the intercom, his eyes upon it. “Perhaps you’d like us to come over there and show you how to start your craft?”

The voice cackled. “Check your long-range trackers, boy, for you’ll need them to find me.”

Evod swatted the intercom switch, clicking it off. “Don’t listen to him, Nevar. This craft is as fast as anyone here.”

“I know,” Nevar mumbled then thought, That’s what I’m afraid of.

A referee ducked his head into their craft. “Your turn for the lineup,” he said.

Evod nodded and then glanced at Nevar. The siblings embraced. “May fortune be with you,” he said. “Remember our father.”

With that, he stepped down the craft’s planks, and Nevar closed the door. She focused on the readouts running across her compuvisor and ordered the ship to start.

The craft’s floor vibrated as a hum emanated from its central core. In a sense, the ship was never “off,” she knew; the artificial singularities always existed in a constant counterbalance against one another even when the craft was not moving, and a computer constantly monitored the precarious symmetry. A state of steadiness required the infinitesimally small gravity wells to wheel around one another. Maneuvering was merely a matter of adjusting the rotational rate of one singularity against the other, increasing or decreasing their spin in an equilibrium-controlled speed. That was more difficult to do than to describe, however, as the gravity fluxes between the two allowed the ship to move only in curves, never in straight lines.

The craft soared into the heavens. Flicking the intercom back on, Never listened intently for the referee’s instructions.

“Nevar, are you there? Nevar?” It was Evod.

“I am here.”

“Good, you did not forget the comm net. Remember, Nevar, ride the tidal forces. Adjust in advance for other craft as well asteroids caught in your –”

She whacked off the intercom switch. “Computer, block all further transmissions from Evod until further instructions.”

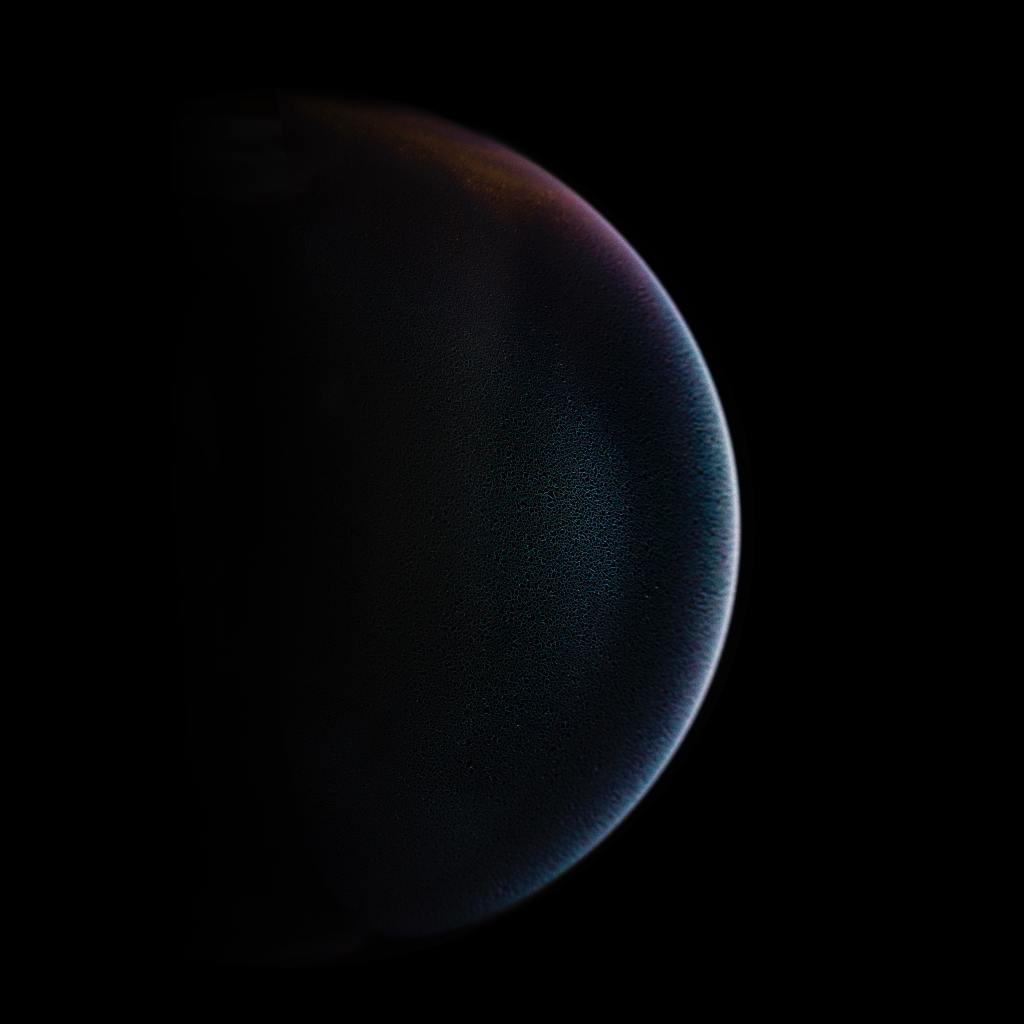

Settling into line with several dozen other craft high above the planet, Nevar examined the black hole ahead. It had the diameter of a mere asteroid. X-rays shot from the white-hot disc at its center, each ring farther out as darkening from white to blue. The small crack in the space-time continuum represented a billion g’s of natural power, all of it sucking in matter that once swallowed vanished forever from the universe.

Over the comm net came the chimes, the same siren call that year after year, century upon century, beckoned a hundred different alien races to the tourney. A hologram of Trope, the highest of seers, appeared on her compuvisor.

“My friends,” he said, his red and white robe shimmering, we are gathered here this day to pay homage to the Prophet, our founder who revealed to all the glory of eternity and salvation. My friends, whom do you seek?”

“We seek the Prophet,” each pilot said in unison, including Nevar, though her stomach quivered.

“Many feared the Prophet’s message,” Trope said. “So they hunted Him, as if He were a dangerous animal, intending to butcher Him. Rather than allow evil to enslave Him and His apostles, He flew into the singularity before us. Through His will alone, the apostles re-emerged unharmed to spread His word. We now live in a time of grace.”

“We seek unity with that grace,” said the pilots, though Nevar, suddenly nauseous, remained quiet.

“Each year, after spreading His word across the far reaches of the galaxy, an apostle returned here to rejoin the Great Prophet. We now submit ourselves to those glorious acts of rejoining.”

“We seek unity with the Prophet,” the pilots said.

The chimes rang once again, and when the last of the three notes sounded, Nevar rammed the craft into drive. It darted forward like light from a nova. Her vision blurred for a moment from the sudden acceleration, but as it cleared she saw on her compuvisor the red glow of other craft shooting in front of her, as if following lines in a single point perspective drawing. Her heart whirled with excitement.

With the voice of a god, the heavenly ballet of stars and dust swirling gracefully and harmoniously in front of Nevar called to her. Behind it, the star field shined like a thousand dancing lights. She breathed in deeply, feeling more alive than ever before. A ship thrust past her, its light distorted and increasingly red as it zoomed. This is not how my father taught me to fly, she thought, and with that she raised the rotation of her craft’s singularities so they bent even more space. Within seconds, she sailed just behind the offending ship and heartbeats later passed it.

Nevar cheered. She knew the craft was superior to most, especially with the modifications made by her father on the last model. Her brother had difficulty understanding the notes left behind but in the end had figured out how to replicate them if not their purpose. Although the adjustments seemed particularly useful for flying through open space, the most difficult portion of the race would be handling the accretion disc, as the craft’s own singularities often resisted the black hole, and the modifications only increased that resistance. Perhaps father had hoped to beat everyone else to the disc, Evod had said.

She veered the craft around a small asteroid caught in the hole’s gravity and then cursed herself for not concentrating. “Adjust in advance!” Evod had told her again and again, and yet here she was, flying tight to the rock rather than riding its gravity well. Such mistakes cost only miniscule amounts of time, but in a race where victory meant salvation, it counted. Rounding the asteroid, her destination loomed in full view, and she wondered what its interior held. The elders said it was a passageway, a tunnel.

She’d never know until entering it, and only the race’s winner was allowed that glory.

Nevar saw three green spacecraft growing in size before her. One of them appeared to be slowing, like flat water below a falls, but she knew it was only an optical illusion. Her craft simply was gaining more quickly on one than on the other two. She checked the readout of her position in the tourney. Fourth. Soon it would be third. She felt a slight chill upon her neck.

Her eyes darted across the array of compuvisor readouts as her craft leaped into third place. She focused on her rear trackers and saw that no other craft were closing. Finally she could achieve what her father had always wanted – victory and the glory that came with it.

“Nevar, are you there?” a voice crackled from the intercom.

“Evod? What are you doing on this frequency?”

“I could not reach you on our normal channel. Is your comm net okay?”

Of course, she suddenly realized, the computer would not block any message sent over the referee’s frequency. That was the rule. A sensible, if annoying, safety precaution, she thought.

“The referee will let me remain on this channel,” Evod said. “Our father’s modifications are working, Nevar, despite the asteroid mishap. You are in third! Soon you will be in first!”

Nevar stared at the sepulcher spiraling before her, at the two crafts ahead, and feared that he was right. “Evod,” she said, “I don’t think I can do this.”

“Yes, Nevar, you can. You are!”

Never suddenly found herself unable to move. All she had to do was increase the rotational rate of her craft’s singularities even more and she’d easily vault ahead of her competitors. If she did not, everything her father and brother believed in would be betrayed. Or would it? Well, at least for her brother it would be so. She thought it great irony that all the pilots were living these next few minutes to simply die the “right” way, and that everyone would be proud of her for achieving something she didn’t want.

They were halfway to the black hole. From far away, it shined like a great rosette against the star field, a magnificent treasure tossed into the sky, but up close it was an evil mouth inhaling the entire universe. The report of a routine diagnostic ran across her compuvisor, announcing that the craft was functioning properly. Then a warning light beeped upon the visor, and she spied a minute singularity on an intercept course. Small bubbles were not uncommon in the race; often a half-mad pilot, straining the field to keep his singularities in check, had no choice but to jettison them or face having his ship collapse in upon itself. There was no honor, no salvation, in such a death.

Never realized that the other craft were adjusting for the discarded gravity well and thus adding to their distances. She knew that most likely her craft would not catch up; accommodating for the singularity this late probably was futile. “Of course,” she said aloud, “I can pull the maneuver father taught me.” Yet she found herself wondering if this was not the perfect excuse for failing, for losing.

Her mind wavered as a sliver of the singularity’s accretion disc appeared at the bottom of the bottom of her compuvisor. There is no proof of what Trope and the others say about the black hole, she thought, just legends. Still, to be alive and face Evod’s chiding for the rest of her life would be almost worse than death.

The accretion disc rose in front of Nevar as Evod screamed her named over the referee’s frequency.

Suddenly she swung the craft in a single orbit about the disc’s equator, and as she completed the cycle, pushed the rotational rates of her artificial singularities to maximum, which shot her in a nearly straight line toward the ships ahead. Nevar’s body jerked, but the inertia dampeners suppressed a great bulk of the thrust. She suddenly found herself back on course and closing again.

Evod hooted and cheered with approval. “What a move!” he shouted, his voice so loud it came out of the intercom distorted. “You’ll make it now! Father would be proud of you!”

Nevar’s body vibrated with excitement. It was a trick usually only stunt pilots pulled.

“Now be careful,” Evod said. “Other craft will be desperate. Watch for them.”

Nevar again checked the rear trackers for ships. She saw none. She knew her brother was right; frequently a craft in second or third place would set itself on collision course with the one in front just to force it out of the way. Glancing forward, she saw the craft immediately ahead of her slowing. The trackers read that a failing computer system was aboard it. She’d have to mount a rescue, for without navigational ability his jettisoning the singularities would do little good. With a firm voice, she ordered her computer to reduce speed.

“No, Nevar, no!” Evod hollered. “Forget him! Focus on the race!”

She slapped at the intercom switch then remembered the comm link could not be severed. “I cannot leave a pilot to die!” she screamed.

“Nevar, he would not stop for you!” her brother said. “If he dies it is because of his own doing. He knew the risks when he entered the race.”

The other ship loomed large in Nevar’s compuvisor. “You mean like how our father’s death was of his own doing?”

A brief silence filled the channel. “Nevar, you are giving up a chance to win!” said Evod, his voice desperate. “Pass him and you’re in second!”

Her craft shuddered as its tidal forces interacted with the gravity well created by the failing craft ahead of her. She suddenly felt compressed, and a tear splashed across her compuvisor. Evod would never forgive her if she did what she knew was right. “What of our father’s memory?” he’d remind her over and over. She still had not worked out the truth of his death, of his sudden last second fling before the craft spiraled past the event horizon and shattered its frame in the black space beyond.

And what of my own life? Nevar thought. She could no longer accept the insanity behind the race. All these people sacrificing time, money, effort, everything …

She ordered the computer to adjust right. The star field again filled the compuvisor.

She thought of her father. She knew why he had veered.

For death.

A warning signal flashed across Nevar’s view, the trackers telling her what she already knew: the restraining field had collapsed on the other ship.

“Nevar, what are you doing?” Evod shouted. “Nevar, are you all right? Come in, Nevar, come in! Nevar, you’re off course!”

The galactic plane’s thick, luminous edge stretched before Nevar, as she ordered her craft to increase speed. She’d have to leave this part of the galaxy or forever be the object of scorn and ridicule. Already she could hear them saying, “The whole T’sohg family, nothing but cowards! What a dishonor to the Great Prophet!”

Either way my existence will be lonely, Never realized. At least this way I’ll be alive. At least this way I’ll honor my father. The craft bolted outward. She sat back, preparing herself for the darkness.

Rob Bignell is the author of more than 80 books and the owner/chief editor of Inventing Reality Editing Service. He has been writing science fiction since he was a boy.